How Do Supreme Courts Review Whether a Law Was Clearly Established

With ii unsigned opinions, the Supreme Court on Monday seemed to double down on a nonsensical and impractical arroyo to qualified immunity.

The court sided with constabulary officers who had been sued for civil rights violations, ruling that the officers involved are entitled to qualified amnesty because in that location was no other case with similar enough facts to put each officer "on notice that his specific deport was unlawful."

In effect, the ii decisions announced Monday mean plaintiffs demand a prior example with well-nigh identical facts in order to overcome qualified immunity and concord public officials accountable.

Qualified immunity:Supreme Court sides with police, overturns denial of immunity in two cases

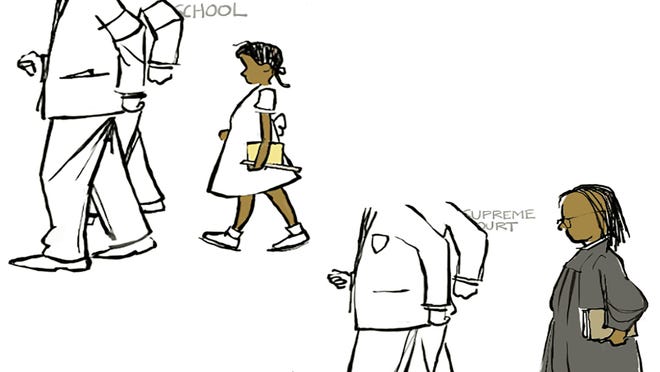

Qualified immunity protects police officers and other government officials from being sued for money damages – even if they accept violated the Constitution – if they accept non violated "clearly established" law. The Supreme Court has made clear that, in nearly cases, the law is not clearly established unless a court previously held nearly identical facts to be unconstitutional.

Some, including myself, had thought the Supreme Court was stepping away from its impossibly restrictive standard when it ruled last Nov, in Taylor 5. Riojas, that no prior courtroom determination was necessary for "obvious" constitutional violations. But the decisions released Monday suggest otherwise.

Why has the Supreme Court adopted such a difficult standard? Because, according to the court, only a prior case with nearly identical facts will put an officer on observe that he has violated the Constitution.

But police officers aren't actually educated about the facts and holdings of cases that "clearly institute" the law, so it makes no sense that victims of police misconduct are denied relief unless and until they tin observe them.

Standards for police apply of strength

Graham v. Connor, decided by the Supreme Courtroom in 1989, sets the standard for police uses of forcefulness. Graham says officers violate the Fourth Amendment only when they employ force that was considerately unreasonable under the totality of the circumstances they faced.

Simply the Supreme Court has made clear that Graham does not "clearly establish" the law. Instead, to defeat a qualified amnesty move, a person must find a case where similar force was used nether similar circumstances. In Brosseau v. Haugen, for example, the Supreme Court decided the plaintiff had to observe a instance with facts that clearly established the officer'due south conduct was unconstitutional under the particular circumstances he faced: "whether to shoot a disturbed felon, attack fugitive capture through vehicular flying, when persons in the firsthand area are at take a chance from that flight."

The Supreme Court has explained that factually similar cases are necessary to put an officer on notice that what he did was wrong. In the court'southward own words, factually similar cases are necessary to "clearly establish" the law because "it is sometimes difficult for an officer to make up one's mind how the relevant legal doctrine ... will utilize to the factual situation the officeholder confronts."

But are officers really educated about the facts and holdings of these cases? The answer is an unequivocal no.

Series on qualified immunity:Faces, victims, bug and debates surrounding qualified immunity: A USA TODAY Stance series

Officers don't know 'clearly established' police

I examined hundreds of apply-of-strength policies, trainings and other educational materials received past California police force enforcement officers. I found officers are educated almost watershed decisions like Graham just are not regularly or reliably educated about court decisions interpreting those watershed decisions – the very types of decisions that are necessary to clearly establish the law for qualified immunity purposes.

California police department policy manuals reference or incorporate the constitutional standards from Graham, simply they rarely reference any cases in which Graham was applied. California police officer trainings focus primarily on the wide principles articulated in Graham.

Even if law enforcement were to rely more than heavily on court decisions to educate their officers most the constitutional limits of strength, there could never be plenty fourth dimension to train officers about the thousands of court cases that could conspicuously establish the constabulary for qualified amnesty purposes. And even if an officer did somehow come to learn about the facts and holdings of these decisions, there is no reason to believe they would remember those details or think virtually them during the types of loftier-speed, high-stress interactions that often pb to uses of force. The expectations of detect and reliance baked into the qualified immunity doctrine would still exist unrealistic.

Qualified immunity: Keep or end?

If we finish qualified amnesty, officers will still not violate the Constitution if they act reasonably considering courts will continue to appraise whether an officer's decision to use force was reasonable under the framework supplied by Graham – which requires that courts consider the totality of the circumstances non "with the 20/20 vision of hindsight" but with the recognition that "police officers are oft forced to make split-second judgments – in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and quickly evolving – virtually the amount of forcefulness that is necessary in a detail state of affairs."

But if we proceed qualified immunity, the definition of "clearly established law" should be changed to reflect how officers are actually educated almost the scope of their authorisation.

If the goal of qualified immunity is to give officers fair notice, and they are on find of watershed decisions like Graham – simply not educated near the facts and holdings of courtroom decisions applying Graham – and then "clearly established constabulary" should be defined much more mostly.

Joanna Schwartz is a professor at the UCLA Schoolhouse of Law.

This column is part of a series by the Us TODAY Opinion team examining the outcome of qualified immunity. The project is made possible in part by a grant from Stand Together. Stand Together does not provide editorial input.

Source: https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2021/10/19/qualified-immunity-supreme-court-doubles-down/8506437002/